During Black History Month, we recognize Black child care providers who provide loving care to children across the country and are disproportionately overrepresented in the field of child care. Black home-based child care providers don’t just provide care to children. Their work holds up their communities, and in doing so, they continue a legacy of communal care for Black communities.

The idea of communal care is that members of the community work together to uplift the community that they belong to.

Dr. Crystasany Turner is a fourth-generation early childhood educator and an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. In addition to being a provider, her work has included teaching and research focused on early childhood education for social justice, culturally relevant policy, and Black feminist epistemologies. While she is no longer a direct care provider, Turner sees herself as carrying on an ancestral heritage through her scholarship and research.

“As a mother and an auntie, it’s just understood that Black women care for our families, we care for our communities. It’s a part of our cultural knowledge, our cultural ways of being,” Turner said. “It’s hard to put words around it, but it’s just understood. Those are my kids. They might not have any blood relationship to me, but those are my kids. So, I would definitely say that the understanding of kin work or collectivism is in our bloodline.”

Before colonialism, many African societies were structured to care for the community as a whole, which included caring for and raising the community’s children.

In Arlene Edwards’s 2000 research, “Community Mothering: The Relationship Between Mothering and the Community Work of Black Women,” she explains that community mothering is a natural evolution from the role of the “othermother,” which is taking responsibility for a child who is not your own. Community mothering, on the other hand, is described as viewing “the Black community as a group of relatives and other friends whose interest should be advanced, and promoted at all times, under all conditions.”

Although communal care has been part of Black culture for centuries, it’s also important to contextualize what Black women caring for children in the United States has meant historically: Black enslaved women were forced to care for the children of the slaveholders and even after slavery, were often forced into domestic employment for decades after that. The lasting effects of chattel slavery in the U.S. can still be seen in the child care sector today, with early care and education being one of the most underpaid fields in the country and having a workforce overrepresented by women of color.

“Thinking about why Black women have had to take on this onus: We love our babies, but at the same time, this is a responsibility that was put on us, and this way of being is something that is a cultural way of being that was created because of so many layers and layers and layers of oppression … because history has told us that nobody else is going to take care of our communities like we do.”

Turner’s grandmother, Margaret Roberson, created her family child care business more than 30 years ago, but in addition to providing child care, what Roberson did was provide a safe space for families.

“Witnessing it happening as a child, I just remember the relationships that she built with the children, of course, but also it was so much more than just child care. It was kitchen table talks with mothers. And so numerous times I would see moms come in crying, having a situation that they wanted to talk out,” Turner said. “So she truly became another mother for a lot of the mothers and the fathers that were in the program, in addition to the work that she did with the children. And she was constantly sowing into people’s lives, whether it be spiritual guidance, whether it just be day-to-day counsel.”

If you talk to current home-based child care providers and the families they serve, that dynamic can be found throughout various communities.

“We don’t just teach history in February. We teach it 365 days a year. As long as they’re here with me, they’re going to know who they are and know their value and know where they come from and where they can go, and who they can be.”

Brenda Campbell

Danielle Caldwell, a Black home-based child care provider in Durham, North Carolina, sees providers as “balms” and “bridges” in their communities.

“We know about Big Mama who is the staple in the community. But a lot of Black home-based child care providers are that in the community, right? We’re counselors. We are social services. We bridge that gap when those families don’t have the funds, usually in January after they have splurged a little bit from Christmas. We are the ones that take the brunt of those things,” she said.

“Because of the culture and how we understand the culture, what might be off-putting to some is not necessarily off-putting to us. We give grace in terms of behavior and things that might be concerning or troubling in other environments.”

In Turner’s 2022 research, “Black Family Childcare Providers’ Roles as Community Mothers During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” she explains the ways in which Black child care providers took on roles in their larger community during the early onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Black early educators and care providers’ kinwork or ‘community mothering’ is a sort of activism that maintains Black culture, cultivates resilience against oppression and social disenfranchisement, and empowers the next generation,” she wrote. “This work is a continuation of Black women’s legacy of going beyond child care to engage in community activism and address the diverse needs of Black children and families.”

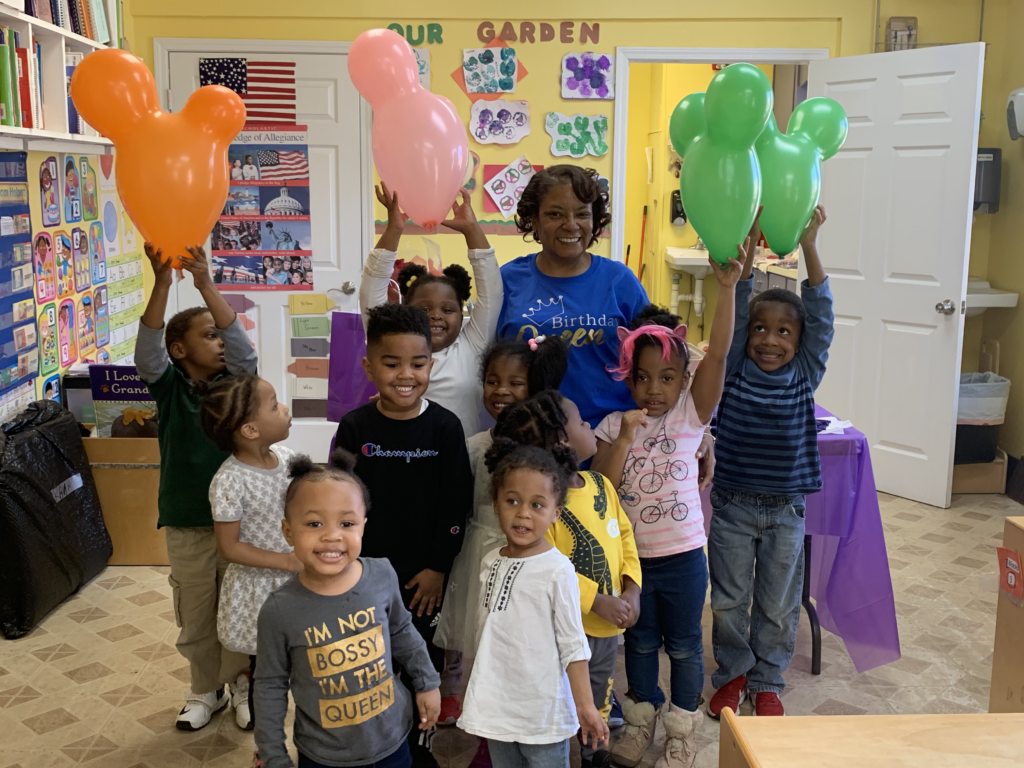

Brenda Campbell, a home-based child care provider in Charlotte, North Carolina, actively engages in this activism in her child care program. And she even considers caring for young Black children, and specifically Black boys, as her specialty of care. For Brenda, part of loving Black children is making sure they know who they are and what their history is.

“We don’t just teach history in February. We teach it 365 days a year. As long as they’re here with me, they’re going to know who they are and know their value and know where they come from and where they can go, and who they can be.”