Last month I interviewed childcare experts and parents to find out how home-based care meets the developmental needs of babies, toddlers, and preschoolers. Home-based child care, they agree, provides a consistent, family-like environment where kids thrive and learn.

Now, as a parent who chose HBCC for my own kids, I also wanted to hear firsthand from the children who spent their early years in home-based care. What do kids think? In this piece I talk to Liam (7) Cole (17) and Brooke (15), graduates of Benu’s Preschool in Concord, California, as well as my own son Zak (24), who went to Ms. Patty’s House in Cullowhee, North Carolina, and Venette (34), a Home Grown staff member who attended a home-based child care program in West Palm Beach, Florida.

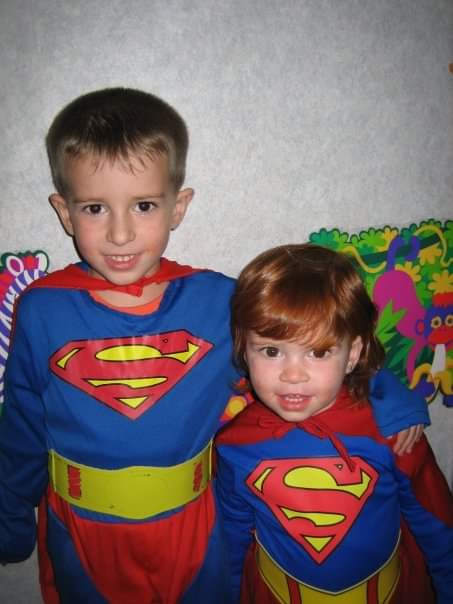

It’s hard for any of us to remember much from our toddler days, but these “home-grown” sages had a lot of wise words about their superhero caretakers. I started with my own son Zak, who is now a graduate student in biochemistry at Scripps Research Institute. He was in the lab when I called to ask, “What do you remember about Ms. Patty’s?”

He was stumped at first, hard-pressed to recall specific events from more than 20 years ago, but then he noted, “I do remember that I loved being at Ms. Patty’s. It was like home–comforting and fun.” That sentiment rang true for other children as well. Home-based child care was a place they loved to be, a place that generated what Venette calls “warm feelings and a hug, where people cared about you and you cared about them.” It’s also a place where these children learned essential social and emotional skills they still use in school, work, and life.

Feel Your Feelings

“Sometimes in my little ages, like two and three, I was a little bit naughty,” explains Liam Cobb, who is now a big kid of seven. “In those olden days when I got upset, my teacher Benu would ask me if I needed to go to the Crying Room.” Taking a time out to express his feelings apart from the busy hubbub of kids playing in the main room helped Liam calm down and regroup. Now, he explains that he knows how to do that without a crying room. “I just breathe and tell myself that, you know, Liam, your worries will be over in a few minutes.”

Liam has learned Self-regulation, a key social and emotional skill that helps children succeed in school situations that often involve waiting, taking turns, and talking through conflict. Liam learned it explicitly and early at Benu’s Preschool, where Benu Chhabra has been taking care of children for 22 years.

Be a Friend and Role Model

“Benu always said ‘use your words,’ explains Brooke Kemper, a smiling 15-year-old who attended Benu’s Preschool for the first five years of her life. “You can’t just be that one mean girl that sits in the corner. She always insisted that we be kind to each other and work together and just like act like everyone was our friend, not just that one favorite person.”

Cole, Brooke’s big brother, now 17, agrees. “I remember feeling some responsibility to be a role model for the younger kids, showing them how they should be acting by the time they were ready to go up to big kids’ school.” That sense of responsibility served Cole well in elementary school, though he also remembers being surprised that everyone in his kindergarten class was the same age and pretty much at the same skill level. “So what I learned was that if you’re going to do something, you gotta do it right or at least try hard. You can be a leader by example, even with your same-age peers.”

Have Fun and Be Fair

Cole, Brooke, Liam, and Venette all extol the value of the mixed-age setting of home-based care, where a family-like setting encourages them to learn from others, help others, lead by example, and value each person in a diverse community. They also note that the balance of free play and more structured activities like crafts in their preschool environment bolstered their creativity and sense of fair play.

Benu’s playground was a place to “try to ride the bike or play around with a basketball,” says Cole. “You learned to make your own fun and create a game with other kids.” “For me, it was the crafts she did with us, and coloring,” remembers Brooke. Ten years later, Brooke shares her creativity with younger kids by helping her former teacher prepare for an annual summer barbecue. “Actually providing some help rather than being a nuisance is important,” says Brooke. “I guess I learned that from Benu and I’m still learning it.”

For Zak “creativity,” has the added bonus of “helping you get out of a rut and get motivated again when things go poorly.” In Miss Patty’s woodsy backyard, Zak experimented a lot with dirt, sticks, and bugs. “Free play forces you to organize yourself,” he concludes philosophically. “You don’t have any rules to work within, so you’re in charge of yourself and you have to choose your own direction. Having that agency has really been important in graduate school because I can maintain a sense of direction and purpose and keep going even when a big project gets pretty messy. . . . Which it always does.”

Try Something New . . . then Try It Again

A small and consistent group in a family setting taught these young people to be kind to others and responsible for themselves. “It’s where I learned to value community,” says Venette. “That sense of community has shaped how I view everything from work to personal relationships, just how important it is to stay connected and to build community with those around you.”

“But what do you remember about learning your letters or numbers, the bread and butter of packaged pre-school curricula?” I inquired. “I remember we had Spanish lessons,” chimes in Cole, “which was a good exposure to another language.”

“And Benu always shared her Indian culture as well as all the holidays and culture,” adds Brooke. Cross-culture content delivered through holiday celebrations, reading aloud, and valuing children’s own heritages and languages was a hallmark of many home-based providers I talked to.

Wise seven-year-old Liam notes that being “open-minded” goes beyond exposing children to new ideas and cultures. ”It also means that I’m willing to try new things now that I might have a problem with at first.” Trying new things, and persevering through the unfamiliar and even through first failures is a critical skill all of these kids learned in home-based care.

Liam, who spent his kindergarten year doing virtual school, explains that having to do homework and stick it out through the full day of in-person school for first grade has been an adjustment, one he is still working on. With “perseverance,” he’s made it through the first grade and even made friends with some of the kids who “were in the bully group” at afterschool.

Thanks to Benu’s care, Liam, whose mom describes him as an anxious and timid toddler, has grown into a confident upstander among his peers. “Even some of the kids who are in the bully group were getting bullied by each other,” he observes. “And maybe they learned some things from me because I stood up for the younger kids who were in kindergarten and now we are even being friends.”

For teenagers Brooke and Cole, transitioning from adolescence to adulthood is a big step into new and bigger challenges. “To make it through,” says Brooke, “I need to have a game plan, and I need to make friends and kind of network. So those collaboration skills I learned way back in preschool, those will help me.”

Find the Best Part of Everything

Her big brother’s game plan in the short term is college. “I think you’ve got to have some perseverance skills and some grit. You’ve got to be able to overcome your problems, like not having the best teacher or professor in college, and work through them, or else you’re gonna drown. You’ve just got to find the best part of whatever it is.”

Finding the best part is something all of these kids learned all the way back in preschool from home-based caregivers who created places where little people experienced kindness, creativity, responsibility, and community. “In preschool,” Zak notes, “you can learn how to put blocks into block-shaped holes, which develops your spatial awareness, and that’s good. That kind of thing is important, but it doesn’t prepare you for a totally new situation. What helps you more, and will always help you in your life, are the coping skills. When I get really stuck, I take a step back and look at things from a broader perspective and try to figure out why I’m trying to do something or, you know, if there’s a completely different strategy I can apply. You might not hone that skill as much in a one-size-fits-all child-care center where everyone just follows the leader. So you have to struggle, and a place like Ms. Patty’s gives you a safe and encouraging place to do it.